Earlier today, I led a 90 minute discussion of themes from my recent book on disability with a dozen or so faculty and staff at the college. It was a really encouraging discussion in a number of ways and I hope to be able to make a video of it available in the future. But here I want to note one of the issues I talked about, which I called ‘the curse of good intentions’.

One of the ways we go wrong with respect to excluding people (with disabilities or because of their race or …) is that we often think our intentions matter more than they really do. Don’t get me wrong, I think that intentions matter. I think it’s less problematic for someone to unintentionally exclude me than to intentionally exclude me. But intentions aren’t all that matter. Intentions often go really wrong. As I said today, it was often good but incredibly misguided intentions that led parents to send their disabled children away to institutions like Willowbrook.

Good intentions don’t exonerate. The ‘curse of good intentions’ is that we often think they do.

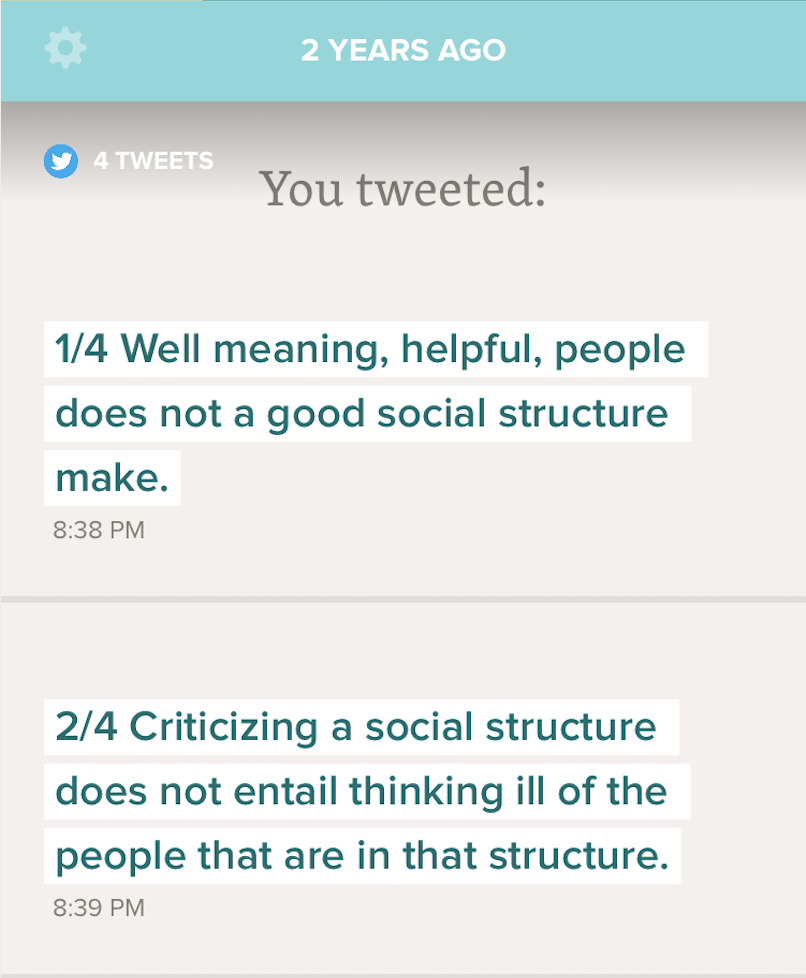

Tonight Timehop reminded me of this series of tweets I wrote two years ago after advocating for a student in an IEP meeting:

These comments are also related to some of my critiques of the power-dynamics often at work in IEP meetings in my chapter “Public Policy and the Administrative Evil of Special Education.” Those interested can read it HERE. It also contains one of my favorite footnotes in anything I’ve published.

Tonight, in preparing for my philosophy of religion class tomorrow in which we’ll discuss a paper by theologian James Cone on “Theology’s Great Sin,” I again came across these related words:

It is important to make a distinction between personal prejudices and structural racism (p. 144).

Cone recognized that one need not have racist intentions in order to contribute to structural racism. Having good intentions sometimes makes it harder for us to recognize the structural barriers, burdens, or harms that we’re contributing to. And when we appeal to our mere good intentions to exonerate ourselves, we become part of the problem.