This post was originally published on Claire Crisp’s blog.

I’m sitting in the waiting room while my seven-year-old son is in OT. My five-year-old daughter is sitting beside me, trying to learn to read. She’s sad because she doesn’t get to have therapy. Her reaction strikes me as both sweet and innocent. She doesn’t realize, yet, that he’s disabled. But she will all too soon.

She finds the word ‘the’ inexplicably hard to read. And I’m losing my patience, not really with her but with the form I’m filling out. It’s a disability enventory, of the kind that we’ve had to fill out all too often. But today is an especially bad day because we’re having to appeal his therapy budget. His access to therapy and funding depend on our answers. They matter.

I want to scream at the form. It’s assanine. Six pages of questions.

I’m frustrated. I post a picture to Facebook expressing my angst

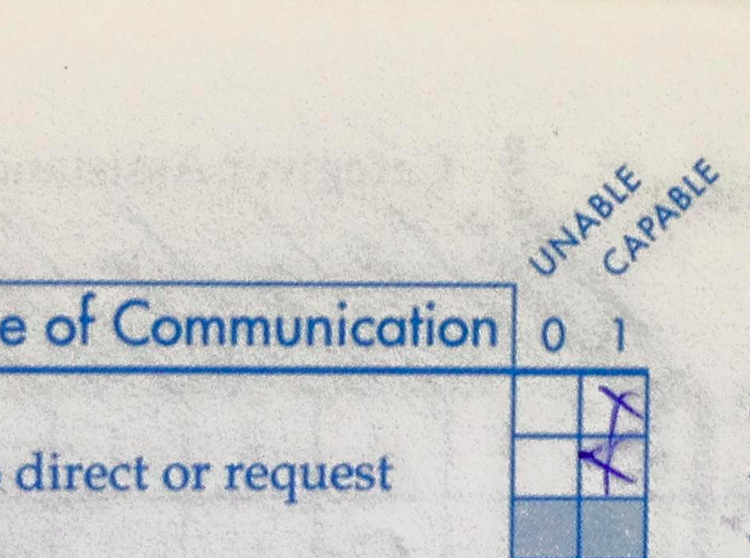

Under it I write: “Filing our disability inventories is infuriating, in part because a child can be ‘capable’ of something but only rarely demonstrate that capacity independently.”

Is he capable of initiating social play? Capable of getting into the tub without assistance? Capable of fastening his pants? Well, in a way he’s capable. He’s done it once or twice.

But he struggles so hard at other times that our generally sweet and couragous boy is reduced to tears that he doesn’t understand. What kind of answer do they want? How do I deal with the uncertainty of not knowing what he needs, the frustration of not knowing how to answer. How best to help him. How best to love him.

Comments to my post on Facebook start rolling in before I’m even halfway through the form.

“0 and 1? Come on now,” writes my good friend Neal. He sees the problem with such a scale. Why can’t those requiring the form?

It’s hard to quantify our son in the way we’re required to. It’s hard to quantify our sorrow, the emotional toll, the years of uncertainty when we had a diagnosis but no prognosis. I think back to earlier inventories and tests, among them an IQ test that we never opened the results from. We didn’t want a number. I can’t reduce what it’s like to be the parent of a multiply disabled child to the sum of numbers on a form or a test. But apparently that’s what I’m supposed to do.

“It can’t simply be a matter of accumulating points, can it?” asks Neal.

Obviously it’s not that simple. But unfortunately its what must be done. The form must be scored.

And the score matters. Checkboxes marking normalcy. Numbers, scores, deciles, and percentiles.

“Wow, that’s depressing.” Yes, Neal; yes it is. And demoralizing. And heart wrenching. And frustrating.

And …..

Another friend asks: “How does putting these kids into these nifty little boxes help? I would just leave them all blank.”

Part of me appreciates the sympathy. But I can’t do that. The scores matter. They matter for therapy. For funding. For his IEP.

“Dad, why are you crying?” asks my daughter, looking up from page 11 of “Little Bug.” How do I answer her question? How do I do any of this?

I have to keep in mind that today’s not a good day. It’s been rough. Draining. Others are better. But there are many like today. Too many. But I have to go on. So I go back to checking boxes. And I hope that I never start to think that they capture my son. I hope that I’m not filing them out in a way that prevents us from getting for him what he needs. I hope that someday, I won’t have to fight so hard for him.

But above all, I hope that I never leave sight that he’s worth every moment of it all, hard and demoralizing as it is.